Part 2 of a series on the future of the web

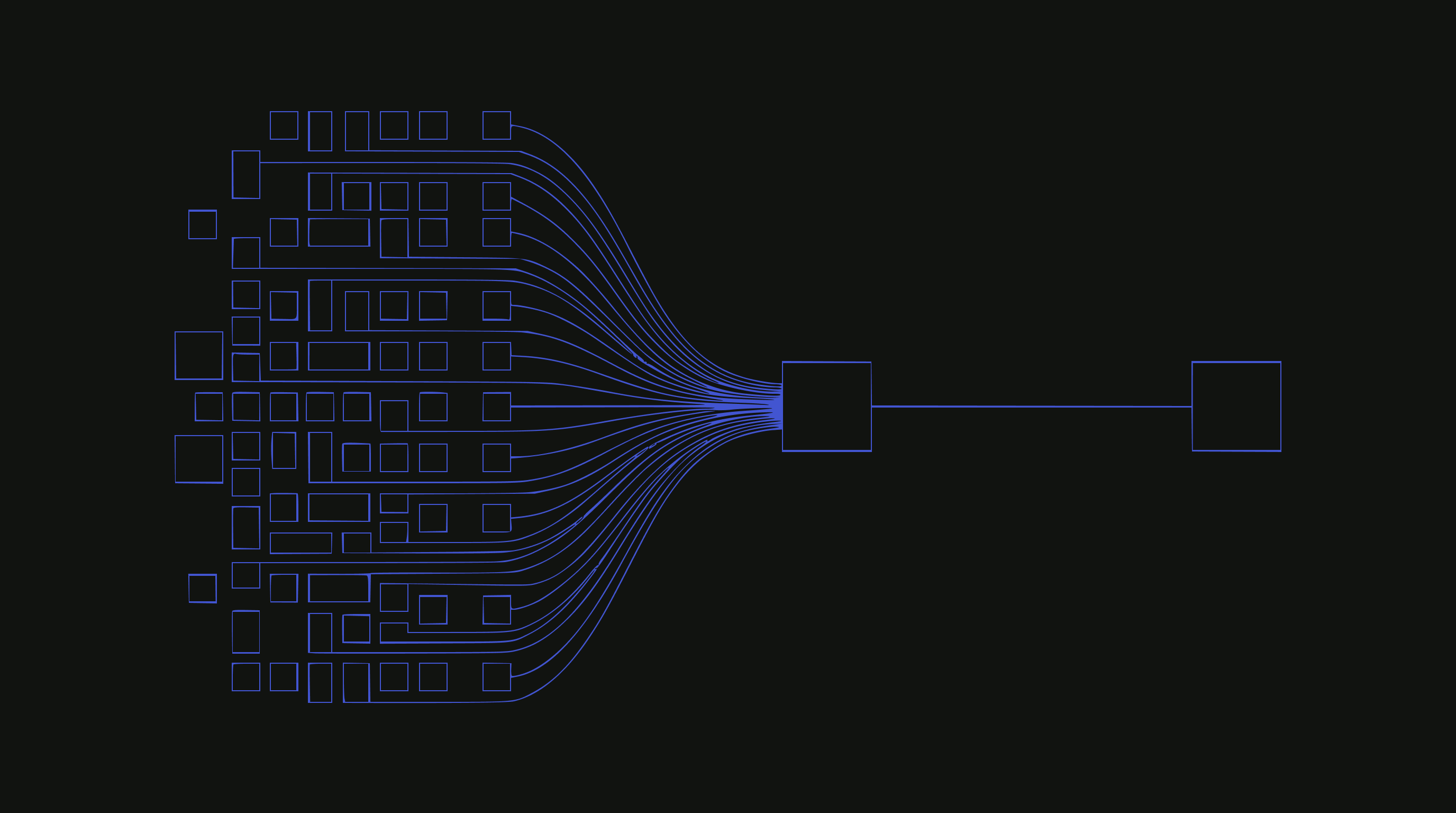

AI reads your content, synthesizes an answer, and the user often doesn’t visit your site. You’re still providing value, but you’re capturing much less of it than you would with a direct visit.

The Consumption Model of the web is changing. The Economic Model hasn’t caught up yet. That’s the transition we’re in right now.

How the Contract is Changing

The traditional web economy ran on a straightforward exchange. Publishers created content. Users visited to read it. That attention got monetized through ads or converted into transactions. Discovery drove attention, attention drove revenue.

The economics of content creation depended on this exchange.

AI synthesis changes this contract. When an intermediary reads your content and delivers the answer directly, some portion of users get what they need without visiting the source. The synthesis draws on your work, but the transaction / unit of value / conversion happens elsewhere.

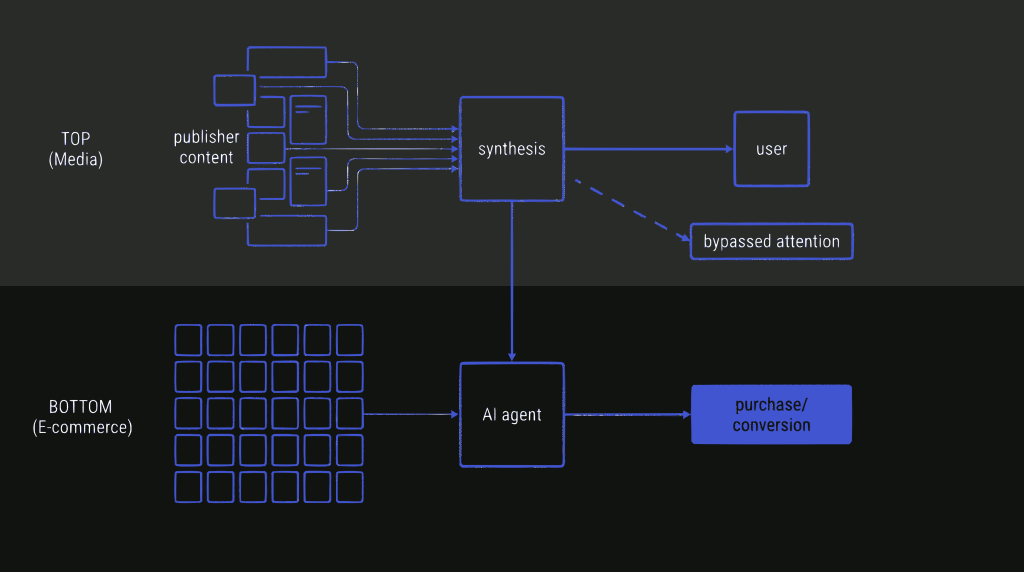

It is important to note that the economics of synthesis have frequently been viewed through a media-heavy lens. We tend to focus on the “publisher” as a newspaper or a blog because that is where the friction is most visible. However, the internet isn’t just media; it is services, business presence, and crucially, e-commerce. Remember, the web is fundamentally a graph of entities.

In the world of e-commerce, the contract changes differently. The goal of a merchant isn’t necessarily time-on-site or reading depth; it is conversion.

If an AI agent can ingest your catalog, determine that your hiking boots are the best fit for the user’s request, and facilitate the transaction, the lack of a “visit” to the homepage becomes less relevant. The economic value is captured in the sale, not the attention. In this scenario, the synthesis engine acts less like a vampire and more like a high-efficiency clerk. Regardless, the disruption is there. But for information providers whose business is selling attention (media), the disruption is fundamental, while for ecommerce, it’s more of an evolution.

This shift is gradual, not binary. Direct visits still happen. Search still sends traffic. But the proportion is changing, and as AI intermediaries become more capable and more widely used, that proportion will continue to shift. Publishers whose revenue depends on attention are feeling this now, and it will become more pronounced over time.

The web will continue to change into the future; this isn’t a single switch being flipped, but a migration.

While gradual, the scale of this shift is already measurable. Wikipedia recently noted that they saw page views decline 9% between 2016 and 2024 while the global internet grew 83%. That’s a 92 percentage point divergence. Cloudflare data shows Anthropic’s crawl-to-refer ratio is nearly 50,000:1. For every visitor AI sends back to a source, its crawlers have harvested tens of thousands of pages. The content flows out. Almost nothing comes back.

The observation sometimes made is that humans also synthesize from multiple sources. That’s true. But when a human synthesizes, they still visit the sites along the way. They see the ads. They might subscribe. The exchange stays intact. When AI synthesizes, the human delegates that traversal to a system, and the system has no inherent reason to send them to the source.

Anecdotally. I and many others now use AI as a search tool. I understand the value of a web page and consistently find myself clicking through the conversation into the source. So while traffic still comes and the behavior of discovery still exists, my (and many folks) behavior is still impacted.

A Coordination Problem

AI synthesis is valuable precisely because it draws on quality sources. Those sources cost money to produce. Journalists, editors, infrastructure, expertise. If sources can’t monetize effectively, they’ll produce less over time. If they produce less, the corpus that AI draws from becomes thinner. The quality of synthesis depends on the quality of what’s being synthesized.

More importantly… AI models in isolation can’t solve the challenge of real-time utility. If a user asks, “What are the events going on in Charlotte, North Carolina in January 2026?”, an AI model cannot hallucinate the answer. It requires a news report, a calendar, or a structured data feed from a local organization in Charlotte to answer that question. It needs to retrieve that specific calendar to answer the user.

This creates a coordination problem with aligned incentives. AI providers benefit from high-quality, up-to-the-minute content existing. Publishers benefit from compensation for their work. Users benefit from accurate answers rather than hallucinations.

Everyone’s interests actually point in the same direction once the economics are sorted out.

The current moment is a transition period. The old model still works, but is fading. The new model is being built. There’s uncertainty in the middle. But the destination is clearer than it might seem: a system where content access is tracked, attribution flows back to sources, and compensation follows attribution. There is immense economic value in publishing the information that grounds the AI; we just need the pipes to route that value back to the creator.

The Collective Model

The music industry went through a similar transition when streaming unbundled albums.

The consumption model changed. Ownership gave way to streaming. Individual songs could be purchased instead of full albums.

The economic model had to change too, but the music industry had something publishing doesn’t have yet: collective organizations that already existed. ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC had been tracking plays and distributing royalties since the early 20th century. When Spotify arrived, the infrastructure for collective bargaining was already in place. Spotify pays into the system, the system pays out to artists.

The economics of that unbundling are a helpful reference for us focused on the open web. Research from Harvard Business School found that as digital music buying increased, album sales dropped significantly while song sales grew, but the growth in song sales never compensated for the lost album revenue. Each album no longer purchased was effectively traded in for one or two individual songs. The unbundling created value for consumers at the expense of producers, until the collective infrastructure caught up.

Publishing is largely in the middle of figuring out that this infrastructure needs to exist for itself. We are seeing the early fruits of that requirement surfacing now.

One example is RSL (Really Simple Licensing). Created by the founders of RSS and launched as an official standard in December 2024, it attempts to streamline this friction. Over 1500 media organizations now support it, including the AP, Vox, USA Today, The Guardian, Stack Overflow, and Slate. Cloudflare and Akamai back it as infrastructure partners. CC, Automattic and many others are involved (and I’m on the technical steering committee). The standard includes both pay-per-crawl and pay-per-inference options, with machine-readable licensing via a robots.txt extension.

Licensing definitions are only one layer of the stack, however. A license without an economic transfer mechanism is just a request. If not honored, what’s the point? The collective is forming, and the infrastructure is being built, but there needs to be a lot more development here to match the efficiency of the music industry’s royalty flows.

Attribution Tracking: The “402 Moment”

The collective model only works if you can track who gets credit and route payments efficiently. This points to the necessity of micropayments and rigorous attribution.

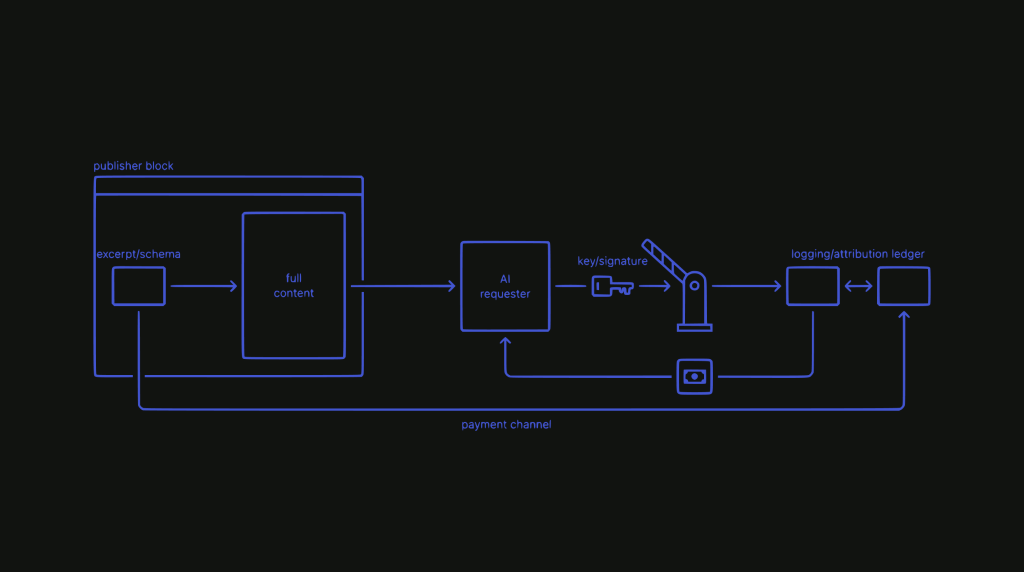

The technical infrastructure for this is now being built. Cloudflare’s AI Crawl Control, which went generally available in late 2024, uses HTTP 402 (Payment Required) as the mechanism. Publishers expose an excerpt and schema for free, enough for discovery and ranking. If an AI system wants full content, it requests access. The request is authenticated: the AI provider presents a signature and verified key. Access is logged, attribution recorded. A fraction of a cent gets distributed per access.

Two-way authentication makes the system trustworthy. The publisher can’t over-report because the AI provider has its own logs. The AI provider can’t under-report because the publisher has access logs. The protocol itself enforces the transaction.

This is the “402 moment” for content. The web always had a status code for “payment required.” And now, there’s a push to create the infrastructure to actually use it.

Training vs. Retrieval

One question that comes up: what about content that was already ingested during training? That’s happened – The models have been trained. Compensation for historical training data is a legal question that will get resolved however it gets resolved.

The more interesting framing for publishers is looking forward: training is positioning; retrieval is revenue.

Being in the training corpus is actually valuable. When an LLM learns from your content during training, it learns that you’re a reputable source. That affects retrieval behavior. The model develops a sense of which sources are authoritative, which are trustworthy, and which produce high-quality information. Training presence is a form of brand positioning within the neural network.

The music industry research found something similar: artists with established reputations suffered less from unbundling than newcomers. Their brand created a buffer. In the AI context, publishers with established authority in the training corpus might see AI systems more willing to direct users to them, cite them, or recommend their premium content. The reputation carries forward.

Retrieval is where the ongoing economics happen. Real-time access to current content, gated behind authentication and micropayments. Training establishes authority. Retrieval generates revenue.

The Premium Content Moat

Not everything needs to be accessible to AI. In fact, I see an immediate and actionable opportunity for publishers is to lean into the things the models cannot generate.

The strategy for publishers: create content that AI cannot create, and keep some of it behind a paywall. Real human synthesis. Product reviews with actual photos from actual testing. Interviews with sources who talked to you and nobody else. Investigative journalism that required months of work. Access to things before they’re released. Video, audio, rich media that carries value beyond what can be summarized.

I’ll always pay for The Information, because it’s a great source, and not something I can “just ask ChatGPT” about.

There’s a nuance here worth noting. The music industry research found that bundles with consistent quality across all items suffered less from unbundling than bundles with one or two hits surrounded by filler. When there was an obvious standout, consumers could easily identify what to cherry-pick. When quality was distributed evenly, the full bundle remained attractive.

The same logic applies to publishers. Sites built around a few high-value pieces surrounded by SEO-optimized filler might suffer disproportionately from AI synthesis. If an AI can easily identify and extract the valuable content while ignoring the rest, the “bundle” of the website falls apart. Publishers with consistently valuable content across their entire catalog, where it’s harder for AI to cherry-pick the hits, might be more protected.

The moat isn’t just about having premium content. It’s about having consistently valuable content that doesn’t lend itself to easy extraction. Again; no flying reporter robots (yet).

Put that content behind a subscription. AI knows it exists but can’t access it. And here’s where the model gets interesting: AI becomes a distribution channel. The synthesis layer can reference your premium content and surface it to users who would benefit. “This answer draws on their free coverage. They have deeper analysis with video and original reporting available through subscription.”

In this view, the AI response becomes an advertisement for the publisher. If the user is already a subscriber, there should be a system where the AI can access that content on their behalf via authenticated tokens and present the full data. If they aren’t, the AI drives the subscription funnel rather than bypassing it.

Why This Can Work for Everyone

AI labs benefit from a functioning content ecosystem. The systems and models are only as good as what they’re trained on and what they can retrieve. A sustainable economic relationship with publishers means higher-quality content continues to be produced, which means better AI products.

Publishers benefit from a new revenue stream that matches the new consumption model. Instead of fighting the shift, they participate in it. Micropayments for access, attribution that flows through the system, premium content that AI can reference but not access.

Users benefit from better answers built on better sources, with clear attribution that lets them dig deeper when they want to.

The Path Forward

The music industry figured this out. Publishing will too.

It requires coordination. Publishers organizing. AI providers participating. Infrastructure for attribution deployed widely enough that it becomes the default.

This is a transition period. The old model and the new model are both partially operating. But the pieces are in place, and they’re coming together. The destination is a system that works better for everyone: creators compensated for their contribution, users getting better answers, and AI making the whole ecosystem more capable.

Next: Agents Enter the Graph